Developing Data Pipelines

November 28, 2020

Someone at work recently asked for some tips on developing data pipelines. They were coming with plenty of experience in data manipulation in Python (filtering, grouping, aggregating, etc) and were used to the fast iteration that you get with in-memory Pandas dataframes. It’s a bit of a transition to a world of distributed calculations where it is much slower to experiment with such data manipulations - but in return for this patience we can scale to processing terabytes of data at a time.

At Spotify, we use Scio for this sort of processing and have thousands of jobs running every day1. (Py)Spark, Scalding, or some other Map/Reduce style framework. I wrote a few tips that I thought might be worth sharing. Some of these are scio-specific, but most of the ideas should generalize2.

In this environment, executing your code (“submitting a job”) takes time, processing lots of data takes time (and money), inspecting results requires hunting down storage locations in some cloud storage bucket, errors are opaque and might take a long time to materialize. I put together a few tips for someone transitioning from a “quick iteration” development process to a “wait this takes how long to run?” development process.

Lean on types

Scala’s type system & compiler are extremely helpful when writing this kind of code. You know that things will probably run reasonably well if it compiles. Python is perfectly happy sending strings to functions that expect integers, even if you have type hints. Scala will break on that and the IDE (intellij is king) helps a lot. That doesn’t mean there aren’t logical errors or the elusive RuntimeException in there!

You’re going to end up chaining a lot of map, filter, groupBy and other operations together. For example, say you have a data set with all of the city populations in the world and want to get all of the state populations within the US. This requires a filter to keep only cities in the US, then a map to extract the state (province) name and population from the City object, then a sumByKey to sum all of the cities in that state.

case class City(country: String, province: String, city: String, population: Int)

// sc.parallelize puts a manually-defined List into an SCollection

val cities :SCollection[City] = sc.parallelize(List(

City("US", "Massachusetts", "Boston", 694583),

City("US", "New York", "New York", 8399000),

City("FR", "Ile de France", "Paris", 2161000)

// ...and all of the rest of the cities

))

val statePopulations: SCollection[(String, Int)] = cities

.filter { row => row.country == "US" } // SCollection[City]

.map { row => (row.province, row.population) } // SCollection[(String, Int)]

.sumByKey // SCollection[(String, Int)]

IDEs like IntelliJ or Visual Studio Code (with the Scala Metals plugin) will tell you what type of data is inside of your SCollection at each step in the chain, as I’ve done in the comments above. The IDE will tell you that statePopulations is in fact a SCollection[(String, Int)] and will tell you if it’s a type mismatch.

Some people like to define the variable first:

val statePopulations: SCollection[(String, Int)] = cities...

And others like to leave the type definition empty and ask the IDE to fill it in once all the code is written. It’s helpful either way.

Tests and debugger

You don’t have to write formal tests first, but they certainly can be helpful if you’re stuck figuring something out. Scio has a JobTest class for tests and other frameworks have equivalents for:

- Specifying input data

- Passing any

args to the job (this is typically how you specify input/output paths) - Checking that the output matches expectations

A simple example of a WordCount job would look like this:

package com.spotify.scio.examples

import com.spotify.scio.io._

import com.spotify.scio.testing._

class WordCountTest extends PipelineSpec {

val inData: Seq[String] = Seq("a b c d e", "a b a b", "")

val expected: Seq[String] = Seq("a: 3", "b: 3", "c: 1", "d: 1", "e: 1")

"WordCount" should "count correctly" in {

JobTest[com.spotify.scio.examples.WordCount.type]

.args("--input=in.txt", "--output=out.txt")

.input(TextIO("in.txt"), inData)

.output(TextIO("out.txt"))(coll => coll should containInAnyOrder(expected))

.run()

}

}

You can run the test using an IDE debugger and place breakpoints in the Scio job to make sure the values are what you expect at various points in the pipeline. This is probably going to be most similar to the iterative experience in a Jupyter notebook. Setting up all of the mocked test data can be annoying (especially if your input data is a complex format with lots of embedded records). For good, reliable code you’ll write these tests eventually anyway!

Use a lot of counters.

There are different types of counters that you can increment on certain conditions to make sure you do/don’t see what you are looking for. Some of the counters that Scio provides are:

- Incremental counter to be incremented inside the pipeline (the most common use case that I’ve seen)

- Distribution to track min, max, count, sum, mean

- Gauge to track the latest value of a certain metric (this is more useful in a streaming context than batch processing)

For long-term monitoring of data quality, these counters (Hadoop and Spark have similar concepts) can be recorded and monitored. At Spotify, we have a service that can send PagerDuty alerts if certain counter thresholds are not met or are exceeded.

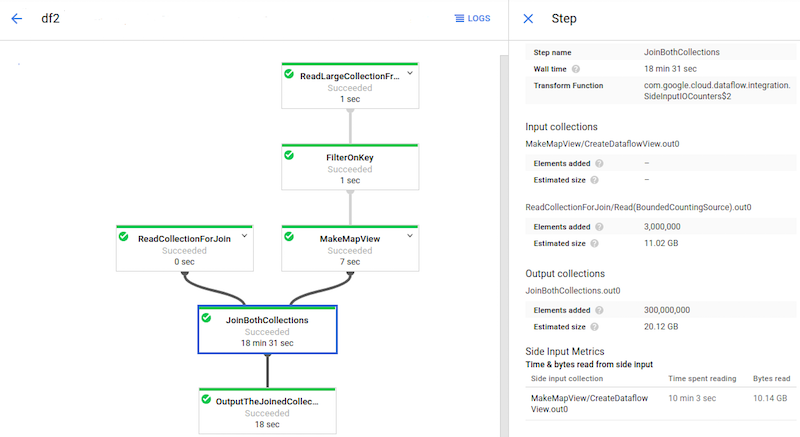

Use the computation graph UI

The image above is a Dataflow computation graph from the Cloud Dataflow docs that we see whenever we run a Scio job. You can click on any node in the Dataflow graph when it is running and see the number of input and output elements. For example, if you’re doing an inner join of two SCollections and you see X input records from one SCollection and Y input records from the other, you should see X (union on key) Y output records.

As the developer, you probably have some intuition of what that number should be, and can confirm it in the job execution UI. If you don’t see what you expect, something could be wrong in the join. This also applies to filter or flatMap functions, and many more.

In Scio, you can also use .withName("a description of this step") on any SCollection. So for example:

sc.parallelize(List(1,2,3,4,5,6,7))

.filter(e => e % 2 == 0)

.withName("remove odd values")

.map( ... the next thing ...)

The filter node in the Dataflow graph will show your supplied name, and you’d expect that the number of output elements should be about half as much as the input.

Output previews to Bigquery

I always save a copy of my result to BQ (or Redshift, or Snowflake, or whatever) when developing pipelines, even if it eventually stores its output in a different format. It lets you visually inspect the results and do all of the tricks you’re used to doing via SQL. You can use @BigQueryType.toTable to annotate any scala case class and then save it as a BQ table

Just be careful not to store decrypted PII in your debugging!

Run on a subset of data

If you can limit the amount of data being read or processed (either by filtering/sampling within the job, or processing one day’s worth of data instead of multiple, etc) that will speed up the iteration process.

Hopefully some of these ideas will be useful for anyone transitioning from working with libraries like pandas or dplyr to a larger, slower, distributed computation environment.

-

Scio is a Scala DSL for Apache Beam, which we run on Google Cloud Dataflow. This means we write our logic as Scala functions and it gets executed on a cluster of machines, which Google provides as a managed service. ↩

-

TLDR for people familiar with at least one of these: Scio/

SCollection== Spark/RDD== Scalding/TypedPipe. ↩